Massage Therapy for Hospitalized Patients Receiving Palliative Care: A (Spectacularly Awesome) Randomized Control Trial

Research done the Healwell way

Cal Cates is the founder of Healwell and a leading advocate for massage therapy in healthcare settings. The Palmer Study was funded by a generous grant from the Palmer Foundation and represents the largest massage dosing study for any patient population.

We were getting into the weeds—as research nerds do—during a lively Q&A at the 2010 International Massage Therapy Research Conference in Seattle. We were discussing where it made the most sense to dedicate our admittedly limited resources. More specifically, we were debating the question, "Which is more important to measure: mechanism or effect?"

During our discussion, my mind took me to an imaginary deserted island where there were just two cans of food. Everyone on the island would have to live on the contents of the can we decided to open. I wondered which can would feed more practitioners: the can that would reveal what massage does (the effect) or the can that would reveal how it does what it does (mechanism)?

There are people doing really important and valuable research who would disagree with me, but I'd open the can about what massage does every single time. Don't get me wrong—I'm dying to know how it works, but I don't think we get to have both in my lifetime, and I'm OK with the how of massage remaining a mystery.

A Study That Delivers on "What" Not "How"

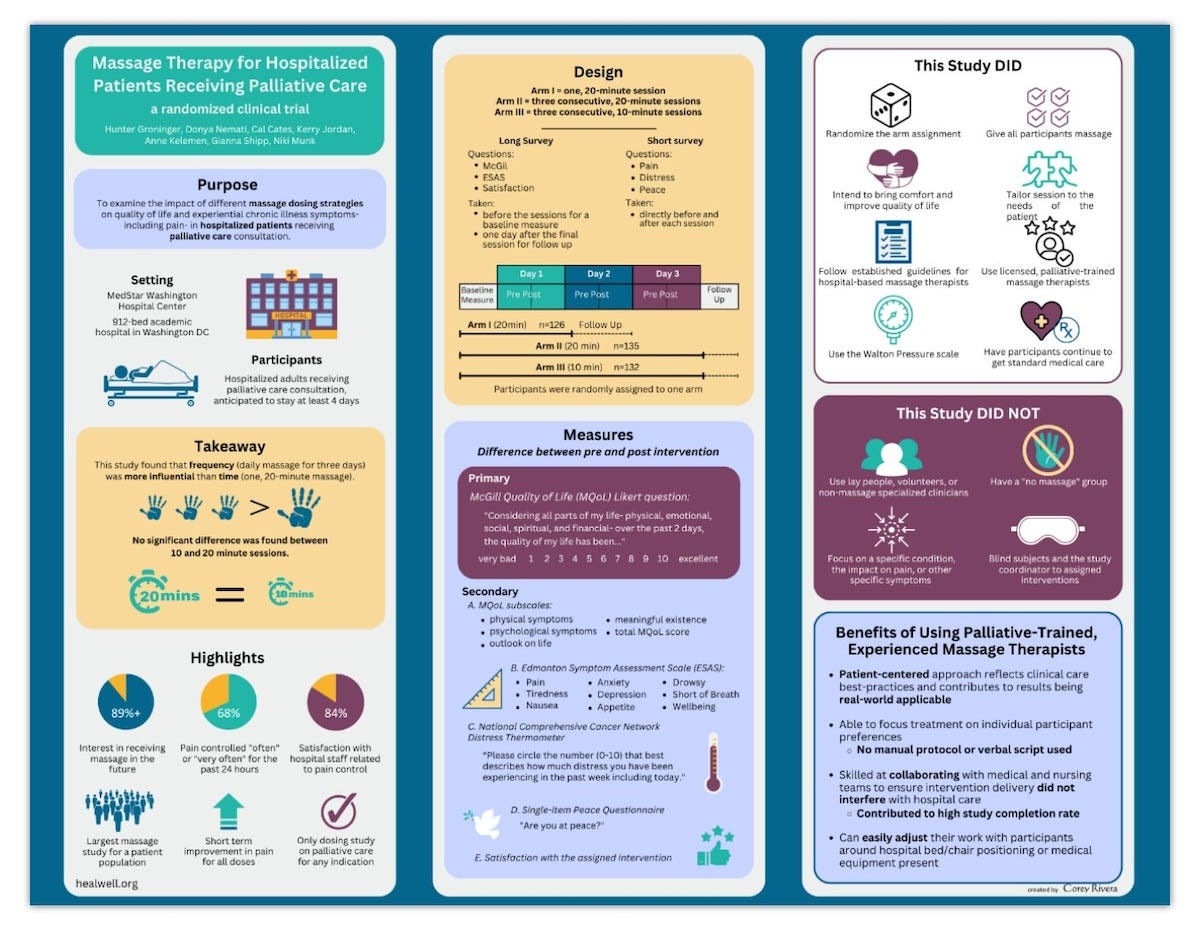

In 2023, Healwell published a paper, Massage Therapy for Hospitalized Patients Receiving Palliative Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial about a study we conducted with our partners at Medstar Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC. The study, lovingly called “The Palmer Study” (named for the family foundation that supplied the $50,000 with which the study was conducted) did exactly that—it focused on what massage does. I don’t think I’m overstating when I say the results are game-changing for our profession.

Over the course of nearly two years, we collected data from over 1,000 massage sessions provided to 417 hospitalized patients. But this wasn't just any population- these were people receiving palliative care—patients whose quality of life was understandably challenged or diminished by serious illnesses ranging from cancer to heart failure to COPD and chronic kidney disease.

Some of the patients in the study knew their lives would likely end as a result of the inevitable progression of disease. Some were recovering from invasive surgeries that resulted in painful healing processes. Others were dealing with months-long intractable infections, fractures, or other common, but challenging complications of progressive, chronic illness.

The Design: Testing Real-World Questions

We designed a three-armed study to answer a variety of questions, including one that hospital administrators actually care about. How much massage therapy (or dose) is needed to make a measurable impact?

Here’s what we used:

Arm I: 10-minute massage daily for three consecutive days

Arm II: 20-minute massage daily for three consecutive days

Arm III: Single 20-minute massage

On some basic level, we wanted to see if we could reasonably tell hospital administrators that an hour of a massage therapist's time could be translated into three to five discrete patient contacts. Years ago, healthcare began to borrow liberally (and detrimentally) from productivity structures and standards intended for automobile manufacturing plants, so when they think about paying for practitioners, they’re wondering how many “units of care” a practitioner can generate in a certain period of time.

But we also wanted to know:

If a patient is lying in a hospital bed, is a single massage as "effective" as a massage every day for three consecutive days?

Is 10 minutes of massage as effective as 20 minutes?

What is the effect of any of these interventions on the nuanced experience of pain and anxiety?

Results That Could Change Everything

The findings were remarkable. All three arms demonstrated within-group improvement for quality of life (which means that people in each group reported an improvement in quality of life, even without being compared to the other two groups). But here's what really matters: frequency trumped duration. We have known this all along, haven’t we?

Massage therapy gets dismissed regularly because the effects are “temporary.” So are the effects of opioids, NSAIDs and every other pharmacological intervention that is standard of care but I’ve yet to hear about a massage that caused constipation or delirium. It turned out that the patients who received massage therapy multiple days in a row had more significant benefit.

The repeated measure analysis (which is a fancy way of saying: when we asked about distress before the massage and then repeated that measure by asking again afterward, we saw x, y and z) revealed that the decrease in distress stuck around until the follow-up questionnaire in a significant level only for Arms I and II (multiple massage sessions) but diminished for Arm III (one massage session). In other words, 10 minutes daily for three days was as effective as 20 minutes daily for three days, and both were superior to a single 20-minute massage.

Let me repeat that because it's crucial: 10-minute sessions were just as effective as 20-minute sessions. And this is where the relativity of time is most definitely on our side. If you’re a massage therapist, or even a regular recipient of massage therapy, you may be thinking, “Ten minutes would be a waste of time. A tease!” I invite you to imagine ten minutes of deep respite in the company of an emotionally regulated, clinically skilled, fully integrated massage therapist on day 38 of your hospital stay. That ten minutes has the potential to do something truly incredible for not just your body, but your mind as well.

Beyond the Numbers: What Patients Actually Experienced

The qualitative findings from our semi-structured interviews with 12 patients, published in our companion paper, "I Didn't Know Massages Could Do That:" A qualitative analysis of the perception of hospitalized patients receiving massage therapy from specially trained massage therapists revealed something profound. Patients shared that the most troublesome and inescapable aspects of their hospitalization were things like loneliness, monotony, difficulty sleeping, and discomfort caused by the invasive nature of frequent blood draws, vitals checks, and procedures.

One of our therapists worked with a patient who had extensive surgery and intense debridement to address an aggressive infection in his knee. The patient's wound was open, so the therapist was unable to work anywhere near the specific site of his most intense pain. After the massage, though, the patient told her, "Yep. I still have pain but it is no longer my predominant sensation."

Massage therapy isn’t magic. Ten minutes of massage therapy isn’t likely to measurably decrease the discrete measure of pain a patient assigns to it on the vaunted 1-10 scale when that pain is centered around a recently debrided, open wound, but ya know what it can do?-- it can make it possible for that person to bear the pain, to be in his body, to take a breath or two or ten.

In line with this patient’s observation, we also found that when comparing the three primary measures of pain, distress, and peacefulness, many patients experienced only a moderate or even no improvement in pain. However, those same patients whose pain measures moved only a little or not at all often enjoyed a multiple point decrease in distress and increase in peacefulness.

These data represent the tip of an incredibly important iceberg. These massage therapists were supporting patients in experiencing their pain differently. They were providing a sense of spaciousness. A sense of profound coping and a return to humanity.

What is possible when a well-trained massage therapist can facilitate a window of real coping and presence in a patient's experience? What if incorporating clinically skilled massage therapists into standard of care means patients are pressing their call buttons less frequently and pressing the buttons on their patient-controlled analgesic pumps less frequently? What if patients who are receiving massage therapy regularly are able to participate more actively in occupational and/or physical therapy activities or goals of care conversations?

We have no idea!...because we’ve never asked.

Why This Population Matters

We didn’t choose palliative care patients because they're easier to study. In fact, this population comes with a unique set of challenges that can make studying them quite difficult. We chose them because they represent the most complex, challenging cases in healthcare. If massage therapy can make a difference here—in this population dealing with advanced illness, complex medical equipment, and profound suffering—it can make a difference anywhere.

The choice to focus on overall quality of life as a primary outcome closely aligns with a participant population receiving palliative care with any underlying diagnosis and for any indication. While other studies have focused on specific diagnoses (cancer, for instance) or specific symptoms (anxiety or pain), our broadened approach better reflects not only the impact of massage therapy delivered by massage therapists in real-world settings, but also real-world patient experience.

The Professional Touch Makes the Difference

It's essential to understand that this study used highly trained massage therapists with considerable experience treating extremely ill patients in hospital settings. This distinguishes our work from the numerous studies that have used non-massage clinicians, undertrained massage therapists or lay people to provide the massage intervention.

The therapists who provided the intervention in the Palmer Study were skilled not only in the hands-on aspects of massage, but also in collaborating with medical and nursing teams to ensure seamless delivery of the intervention within the flow of concomitant hospital care. In addition, they could easily adjust work with participants around hospital bed/chair positioning or medical equipment present.

Studies that don’t use massage therapists to provide the intervention or that employ a strictly scripted protocol are measuring rubbing, not massage therapy.

If you are researching massage therapy, it is essential to have a resource who understands massage therapy from the inside. It is unfortunate that much of massage therapy research has been designed and conducted without this critical element. (For more on this, you might enjoy our paper in the Annals of Palliative Medicine, Massage therapy in palliative care populations: a narrative review of literature from 2012 to 2022; and by “enjoy”, I mean you may find yourself shocked, edified, and inspired.)

Real-World Applications

The busyness of contemporary hospital care doesn't typically lend itself to a traditional 45 or 60-minute massage session. One study found that hospitalized patients receive a median of 3.5 healthcare provider visits per hour. We have also noted, in practice, that longer sessions take us into the territory of diminishing returns when we are working people who are medically frail and chronically ill.

By demonstrating that consecutive daily massage sessions improve quality of life more than a single massage, and that 10-minute sessions are just as effective as 20-minute sessions, our study's findings signal pragmatic strategies to better integrate massage therapists into hospital settings and their busy, complex workflow.

Looking Forward

We don't yet know how moments of manageability and supported coping can affect the overall trajectory of a patient's hospital stay or illness, but there are real possibilities here for augmentation of what is now standard of care. We can begin to look at how these practitioners providing this complex, psychosocial intervention can impact clinical outcomes as well as institutional savings.

What if a massage therapist worked with a patient in advance of a scheduled family meeting?

What if a massage therapist worked with a patient right before or right after a session of physical or occupational therapy?

What if a massage therapist supported a patient in a way that they felt safe to share important information about their own concerns and worries?

What if that massage therapist could then share that information with other members of the care team?

The medical establishment has put massage therapists in a cage match with pharmacologic interventions. We’ll take that bet, but let’s make it a fair fight. The demonstrated impact of relatively small doses of time with a massage therapist suggests that further study is warranted to evaluate the impact of multiple short interventions each day to increase cumulative pain and symptom improvement on par with accepted pharmacologic interventions.

The Bottom Line

When we look at research, there are so many things we can measure and ways we can measure them. Many of the symptoms patients report—lack of peace, need for companionship, difficulty coping, and lack of touch—are things that cannot be reasonably addressed by pharmacology or equipment.

This is where I get really excited. Beyond providing comfort and decreasing symptoms, massage therapists offer something that fills gaps in what medicine can provide. We're not just reducing pain scores; we're changing the lived experience of suffering.

The Palmer Study points encouragingly toward the reality that massage therapy works in the most challenging healthcare settings, with the most complex patients, delivered in practical timeframes that fit real-world constraints. That's not just research—that's a roadmap for the future of our profession.